After years of rumours and premature reports galore, the demolition of Tokyo’s iconic Nakagin Capsule Tower is sadly now underway. Completed in 1972, the building was, and has remained, a striking example of Japanese metabolism. An architectural first, its 140 capsules — measuring 2.5 m by 4.0 m with a 1.3 metre diameter window — were all designed to be removed, allowing them to be individually replaced over time so they could evolve in accordance with societal changes and trends.

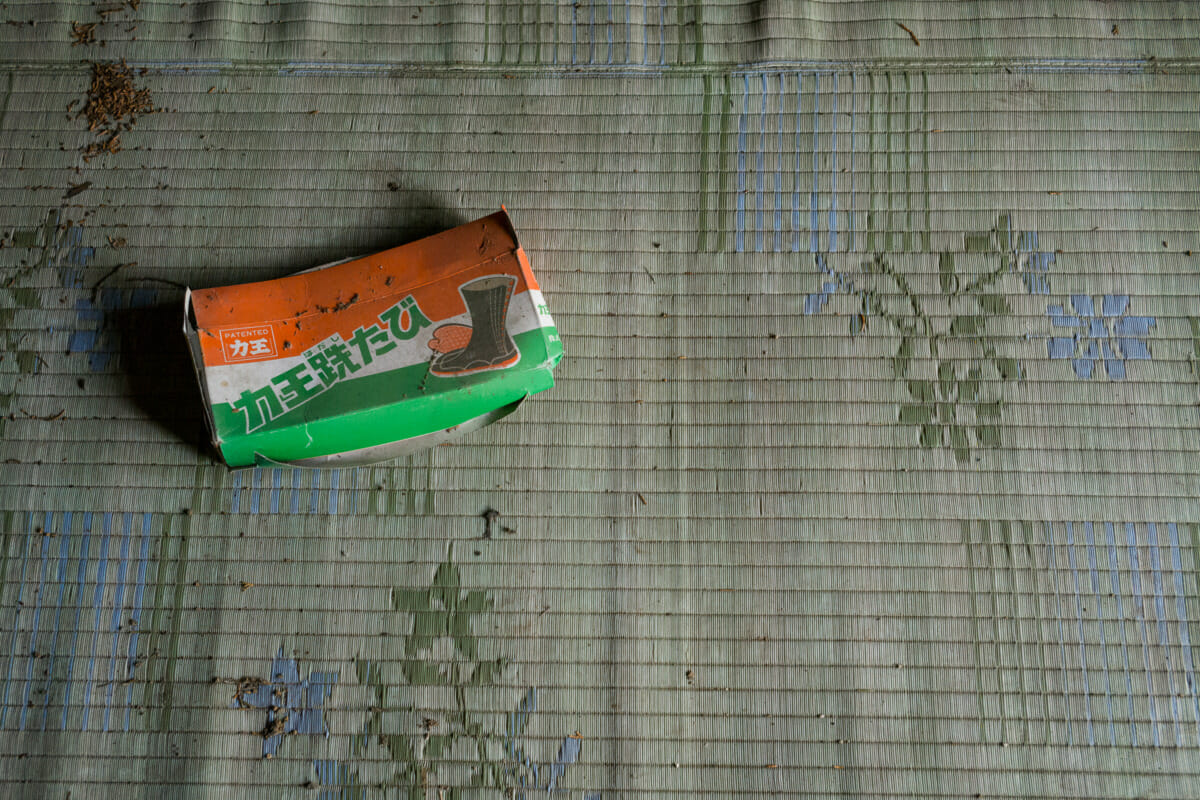

The problem was that never happened, meaning the capsules, and indeed the tower itself, slowly fell into disrepair. Leaks and serious decay were visible everywhere, and even the hot water has been shut off since 2010, forcing residents to use shared, on-site portable shower units. In reference to this, the two first and last shots below were taken a week ago when demolition was already underway, but the interior photos are from a decade ago, and the decline was very obvious back then.

Needless to say there have been campaigns to save it over the years, along with numerous calls for donations, but the Nakagin’s demise always seemed inevitable as the cost of repairs would have been nothing short of astronomical. Yet as impractical as living there must have been in many ways, it was a truly special structure, and there’s no doubt whatsoever that Tokyo will be a less interesting place without it.