This compact row of old Tokyo houses stops me in my tracks every time I see it, and while far more ramshackle and on a much smaller scale, it somehow always reminds me of Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning. With that in mind, my hope has always been to capture a lone, suitably Hopper-like figure looking out of a window. Frustratingly that still hasn’t happened, but a resident stood in her doorway staring down the street will definitely do for now.

The silent homes of a long-abandoned Japanese village

Over the last year or so I’ve posted a few sets of photographs from long-abandoned Japanese mountain villages. There was this incredibly photogenic little hamlet, and then more recently, the time capsule-like quality of a settlement tucked away in the trees.

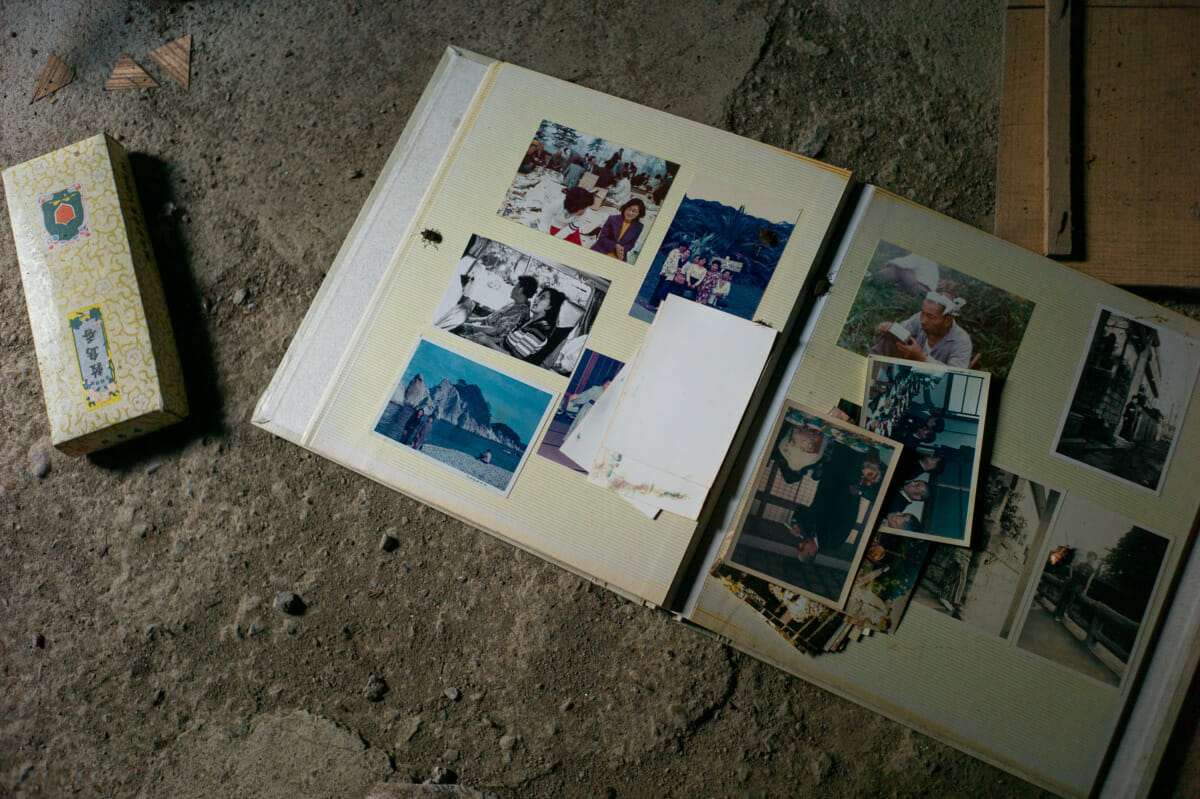

The gathering of houses below, however, is a bit different. Or at least a bit different in the sense that I’ve visited it a couple times, and after recently finding a forgotten photo of a photo from when the village was still occupied, it seemed like a good idea to go back through my shots, do some re-edits, and then put them all together in a single series. A step back in time that was triggered by a much longer look into the past, and as such, I’ve included that old, undated image to round out the set, which sort of brings it all back full circle.

For a bit of background information, the village’s former residents were all hired by the forestry department, and considering the time and location, they would have lived quite isolated lives, with even basics such as food and fuel supplies requiring forward planning. An unusual existence compared to what most people are used to, and unlike their city dwelling compatriots, bears rather crowds or crime would have been a key concern. Day-to-day life that must have been as idilic as it was difficult, yet whatever the small community of workers made of it, human habitation came to an abrupt end in the late 1980s, when presumably due to a lack of employment, everyone simply packed up a few possessions and made their way down the mountain.

A blue-eyed Tokyo host in the darkness and light

Some days are still really quite warm, but there’s finally a genuine sense of autumn in Tokyo, and along with more comfortable temperatures comes some truly wonderful light. The angle and intensity of it is mercifully a world away from that of the summer, so once again it allows for photos like the capture below.

The man, along with the contrast of light and shadow, reminded me of a documentary I’ve mentioned on Tokyo Times before, The Great Happiness Space: Tale of an Osaka Love Thief. A film that for now at least is available on YouTube, and after not seeing it for a long time, a re-watch reminded me of what an informative hour and a bit of viewing it really is.

Shinjuku’s Kabukicho red light district has fascinated me for a long time, and while it has certainly changed and been reduced in size over the years, it’s still an incredibly interesting place to walk around. Like so many others, however, I merely observe — passing through with some knowledge of the area, but little in the way of any real insight into the lives and experiences of those who actually earn their livings there. As such, I can say with reasonable certainty that the man in the photo is a host, but until watching the aforementioned film, I had no real idea of what working in a host club entailed, and even less sense of the surprisingly important part it plays in the lives of the young women who spend their time and money in such establishments. A documentary that does a remarkably honest and often tender job of showing those aspects, plus at the same time it says an awful lot about Japanese society as a whole, and in many ways the human condition itself. Elements that this photo can only try and hint at.

Tokyo memories and loss

This week my wife would have celebrated her 44th birthday. The fact that Akiko isn’t here to do so is still hard to fully grasp, although that isn’t anywhere near as hard as day-to-day life without her. Feelings that aren’t going to change any time soon either, as it’s only a little over 3 months since she died. A period that has felt unreal, and at the same time all too real, as it’s simply impossible not to think about all the meals and conversations we should have enjoyed — not to mention all the similar times we will now never have. Constant, utterly uncontrollable thoughts of what was, and also what might have been. Thoughts that are currently more acute than ever, and yet thoughts that in a slightly more positive way brought me back to the photo below.

It’s an image that somehow seems to encapsulate the past and the present in one simple frame, creating a moment of hope and loss, memory and reality. It was also Akiko’s favourite photo of mine. One she helped create as well, as seeing my original edit, she immediately shook her head and said, “Nah, it has be in black and white”. She was absolutely right of course, as those previously mentioned elements only really work in monochrome — a collaborative approach that now makes the image even more special. Sadly we will never grow old together like the couple briefly captured, but we were lucky enough to be as content as they look, so as time goes on, those memories will hopefully make the present reality that little bit more manageable.

A corrugated old Tokyo house and its colour coordinated owner

Recently there’s been no shortage of photos on these pages documenting houses that have been demolished. There was a whole host of them in this series, and a single, very poignant loss in this post. Such scenes aren’t exaggerations either, as a lot of old Tokyo is very rapidly disappearing, but for now at least, there’s thankfully still a lot to see. Like the house below for example. The shape and corrugated exterior make it as wonderfully ordinary as so many others, and yet on this particular day, the light and the owner’s colour coordinated outfit made it that little bit more special.

The distinct personalities of old and disused Japanese vending machines

Quite why I find them so appealing isn’t easy to explain, but there really is something special about old and disused vending machines. Each one seems to have its own distinct personality, or at the very least a sort of quiet dignity. All of which is utter nonsense of course, as in reality they are simply decaying metal boxes, and yet somehow, in some way, they are also a lot more than that.

Now, whether there’s any truth in any of that is very subjective to say the least, but for me, the beauties below contain elements of everything I’ve tried, and likely failed, to articulate. Slightly older edits of a couple of the photos have appeared on Tokyo Times before. A few of the machines have too, although these are newer, or previously unpublished shots. The others are recent finds. Discoveries that, in their own inexplicable way, made the day they were stumbled upon way more memorable than it would have been otherwise.