A Tokyo mechanic and his amazingly cluttered garage

A retro Tokyo peep show sign

After finally declaring a state of emergency a couple of weeks ago, the Japanese government also announced a series of financial initiatives to ease the strain on those suffering economically due to the coronavirus. The exact details, and perhaps more importantly, eligibility, haven’t been fully disclosed yet, but there is already a refreshingly public campaign to include workers from Japan’s varied world of adult services, as just like so many other industries, they have seen incomes plummet. It’s a group, however, that the government seems intent on excluding, citing the involvement of organised crime and legal issues.

What the result will be remains to be seen, but one person who doesn’t have to worry anymore is the woman photographed below. A well known old school face in Shinjuku’s Kabukicho red light district, it’s probably fair to assume that not only will she have retired from the business, but she’ll have retired full stop.

The demise of a Tokyo danchi, or social housing complex

The golden era of Japanese danchi, or social housing projects, peaked in the early 1970s when the large-scale construction of concrete tower blocks eventually caught up with the huge number of young, urban middle-class families looking to move out to the suburbs.

Influenced by Soviet architecture designed to deal with similar population demands, danchi were relatively cheap and efficient to build, but at the same offered a new kind of lifestyle to a generation of Japanese looking to make a break from the past. Some of them were also massive, visually striking monuments to modernity, that even today, in all their faded glory, still conjure up visions of the future, and perhaps more than anything else, the sense of optimism that once surrounded them. Photographs of one such building can be seen in this series I took earlier in the year, along with a more detailed write-up of the ideas, decline and also adaptation of such accommodation.

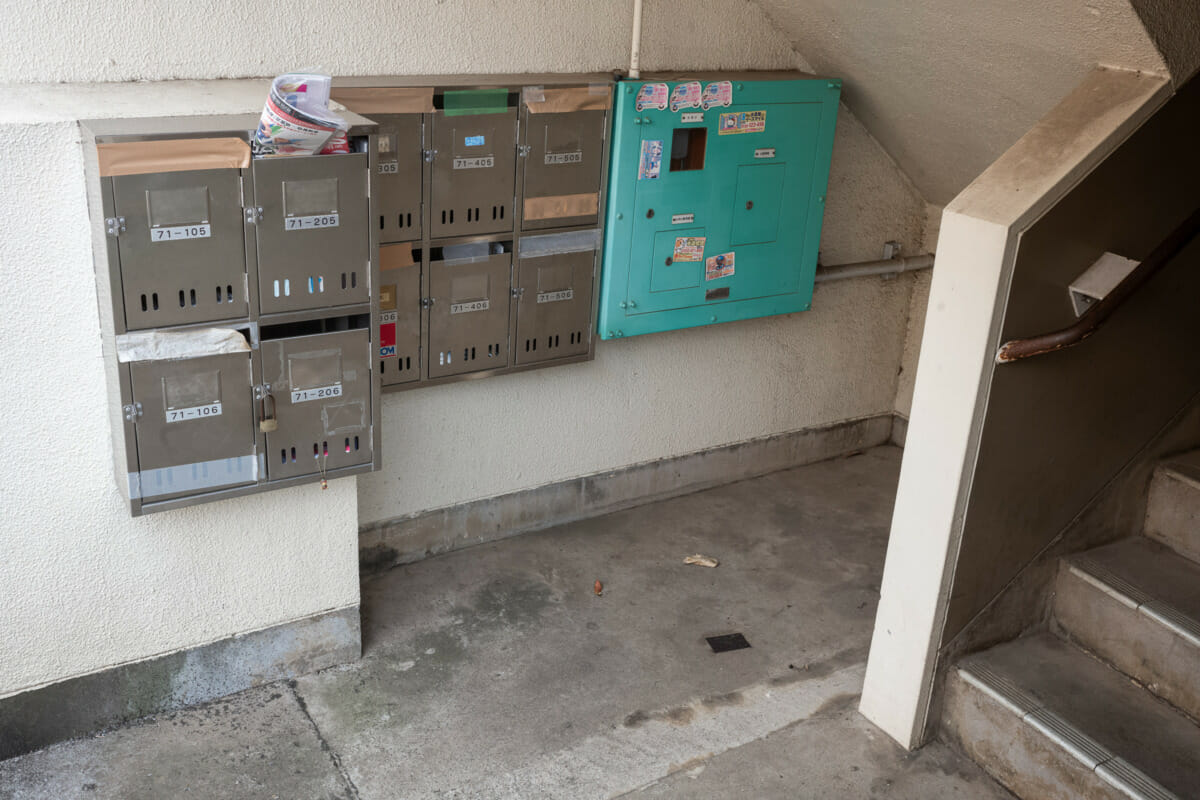

Unlike the building linked to, however, most danchi are much more utilitarian in their appearance, and as well as showing their age, so are many of the people who live in them. Lots of those early residents have grown old in the apartments they once raised families in, and as that generation begins to slowly disappear, so do the actual structures — the ones below being a perfect example. It’s a housing estate near where I live, and on a couple of local walks last week, I had the brief opportunity to document how it looked after everyone had moved out, and before the main demolition crew had moved in.

Padlocks on some of the post boxes suggested that one or two places still hadn’t been handed over, and there was also the occasional visitor taking the last of their possessions away. But workers aside, the area, once alive with the sound of families and friends, was quiet and mostly empty — the only lasting element of its former days being a vague sense of lives lived, and lives that have moved on.